Days after Strava fitness heatmaps were shown to reveal the location of military bases, a Norwegian journalist fooled Strava into revealing the names of some of soldiers and other personnel on those bases.

Strava’s decision to release a heat map visualization of billions of data points recorded from its millions of users is generating plenty of attention for the company – but maybe not the kind company executives planned.

First, eagle eyed Twitter users noted that the training activity and location of military personnel in global bases could be gleaned from countries like Afghanistan and Syria where recreational jogging with fitness trackers is otherwise rare. Highlighting US military supply routes and the outlines of secret bases in bright lines was bad enough. But at least the identities of the device owners were protected. Or were they?

On Wednesday, a Norwegian journalist revealed that with a fudging of the Strava application and some “brute force,” he could unearth the names of some of those soldiers, showing how easily sensitive data can be leaked from these types of apps and sending out aftershocks about the security of the Internet of Things (IoT).

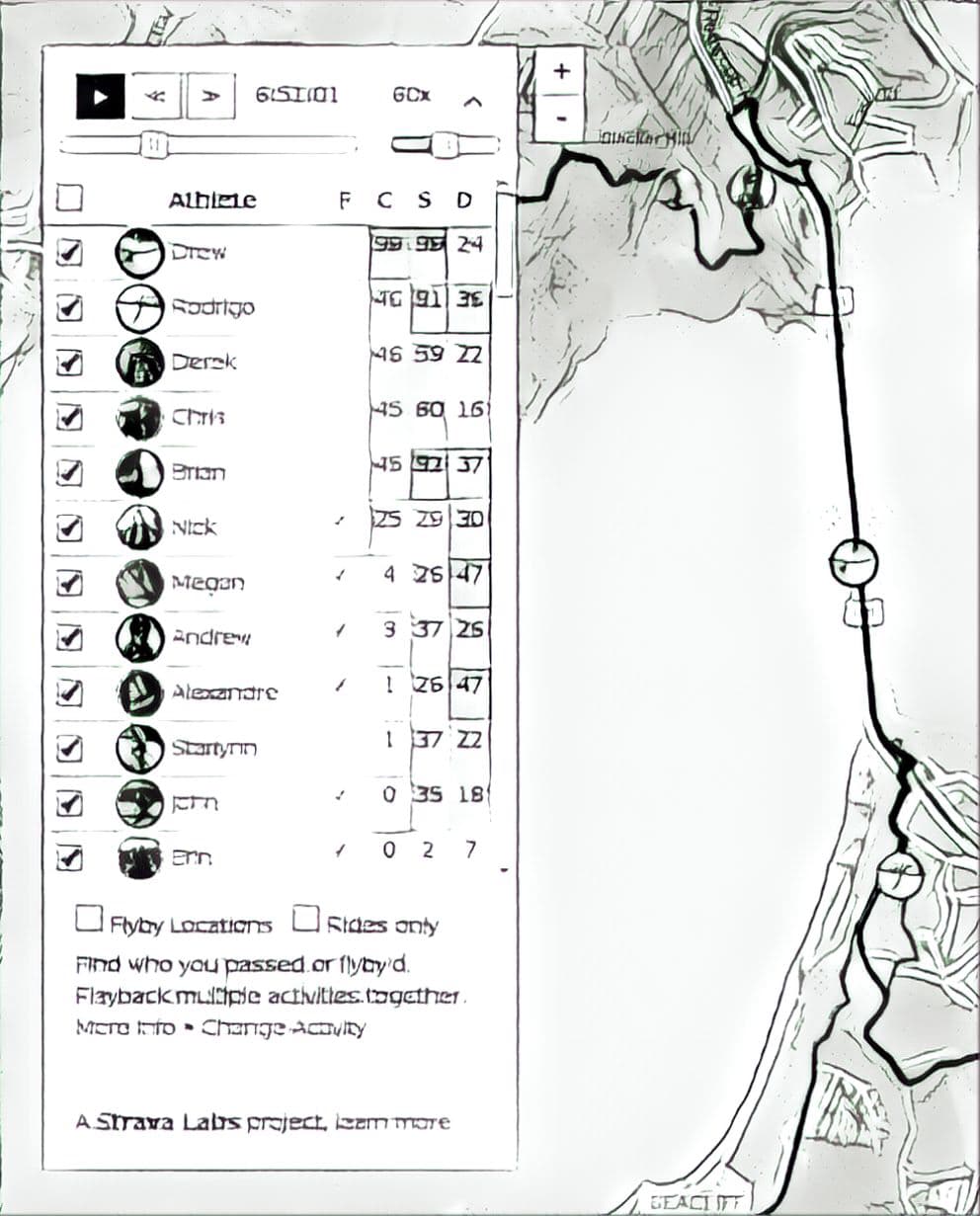

Henrik Lied (@henriklied), a journalist at Norway’s NRKbeta–Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation NRK’s sandbox for technology and media–said the heatmap controversy inspired him to delve a bit further into what other sensitive information could be revealed by making some tweaks to Strava, a fitness social network that allows people to share their running routes and other workout information. By exploiting a Strava feature known as “Flyby” that shows Strava users other Strava users in their immediate proximity, he also reveal the names and identities of the military personnel who generated the data on the heatmap.

Lied revealed the results of his experiment in a blog post early Wednesday. Later, he told Security Ledger that he was inspired to dig deeper because he had a sneaking suspicious the “anonymous” data revealed by the heatmap wasn’t actually so anonymous. “Anonymization is hard, especially at this scale,” Lied told us in an e-mail interview. “It is virtually impossible to fully be able to say that data is anonymized when you use all data as input for your aggregations.”

In the case of the Strava heatmap, Lied and his colleagues realized that some of the lines on the heatmap were single trips, he said. “In other words: Not really aggregate. This made us pretty certain that we would be able to identify someone if we just found the right method.”

Faking Out ‘Flyby’

Lied and his colleagues—who mainly work with testing and implementing new technologies and evolving their company’s digital strategies–knew that their editor is an avid Strava user, so they hit him up for information. He told them about the Flyby feature, which lets Strava users see other users who crossed paths with them around the same time.

“So we developed an hypothesis,” Lied told us. “Maybe we can create fake runs in the areas we’re interested in, and ‘go back in time’ and check for activity in those areas using the Flyby feature.”

His initial idea about how to do this was to use a software defined radio (SDR), and spoof his iPhone into thinking it was actually in Afghanistan. The team soon scrapped that plan “because of a time limitation in how long our SDR can spoof a device in one run–about 5 minutes,” he said.

“We concluded that this would be too time consuming,” Lied explained. “The jogs should ideally be between two and three hours to be able to find as many different people as possible.”

So the researchers tried a different tack, deciding to use a feature of Strava support that allows for GPX uploads of recorded tracks in bulk, he said.

“You can upload 25 GPX files at a time via the website,” Lied told us. “So I sat down and created a script which takes one GPX track as input, and creates 364 versions of the file as output–one file for each day. Each file has small differences in time of day and tiny differences in the track route to be able to catch as many possible routes as possible.”

For each of the areas they focused on, the team uploaded 365 files to Strava, and manually went through the Flyby interface on Strava to see if any other people were in that area at that time, he said. If so, they saved that URL for processing and identification of the individual.

Lied and the team made some simple assumptions as they created nearly 1,000 fake routes, “like the fact that most people don’t go out jogging mid-day in areas where the temperature easily reaches 40 Celsius,” he said on the blog. “Most of our fake trips occurred during dusk or dawn.” After the trips were uploaded, they manually went through each of the routes in Strava Flyby to check for other users in the same area.

The result? Within a couple of hours, Lied had identified 18 people on the map from Norway, Denmark, the United States, France, the Netherlands, Italy and England. In all, the reporters from NRK found the training profiles of 20 persons who have been stationed in military bases in Iraq and Afghanistan. The eighteen who were identified used their full name in the Strava app and NRK was able to positively identify them as military personnel.

Blame the…humans?

Lied stressed to us that his action wasn’t meant to be a critique of Strava’s security, or lack thereof. Rather, it should be an example to the people implementing IoT devices that they should understand the technology before using it—especially when dealing with classified personnel or information.

“My opinion is that the problem is human, and that people should have a better understanding of what the services they use divulge of information,” he told us. “If the military personnel in question had acquainted themselves with how Strava works, they could have opted out of all the parts of Strava which makes it possible to use this technique.”

Faced with the fallout of the heat map issue, Strava executives have urged military personnel to opt out of the heatmap feature. The company’s application has a wide range of privacy settings, including an “Enhanced Privacy Mode” and the ability to create “privacy zones” – geographic areas where you might work out that you don’t want identified such as work or your home.

Default privacy setting is…absolutely no privacy

However, the default privacy setting for the application has Enhanced Privacy Mode disabled, allowing verbose sharing of your information. In short, the default privacy for Strava is no privacy at all. Or, as Strava writes on its blog:

“The basic level is to choose to not use any privacy controls and make your info available publicly, like it would be on Twitter, for example.” (Emphasis added.)

That means public sharing of Strava users’ full name and any shared photos. Other Strava users can follow you and view your activities. The Flyby feature must be specifically opted out of, though Strava said it would be reviewing its privacy policies and settings.

The Flyby feature, in particular, has raised concerns among users about the potential for stalking. A 2015 article on the web site TotalWomensCycling is titled “Strava Flyby: Useful Social Tool or Risk to Vulnerable Cyclists?” and includes testimonials from Strava users who recounted tales of strangers speaking to them by name after having learned it via Strava’s Flyby feature.

The results of Lied’s hack are quite dire indeed for the overall security of fitness apps as well as other mobile apps and connected devices that rapidly are becoming part of the IoT, particularly when global defense or other sensitive information is at stake, he said.“This information can be quite compromising for a lot of people,” Lied warned. “Since a lot of this data seems to come from devices like Fitbit and other kinds of equipment that simply logs your entire day, one might be able to use this data to see where soldiers go when they are off duty, and what kind of training routes they take outside of camps. One can quite easily gather what kind of patrol routes soldiers take, etc.”

At the moment, location-based services seem to be the security weak link for apps like Strava, Lied said. He advised that military personnel think twice before turning on this feature when they’re in a location they might not want to disclose to enemies.

“If you are a special-forces soldier operating clandestinely in a country, your location is not something to broadcast to a commercial, online service built around sharing locations and routes,” he said.

Pingback: Episode 82: the skinny on the Autosploit IoT hacking tool and a GDPR update from the front lines | The Security Ledger

Pingback: Smartphone Users Tracked Even with GPS, WiFi Turned Off | The Security Ledger

Pingback: Fitness Hacker: Under Armour breach affects 150m | The Security Ledger