None of us need a reminder of how difficult the ransomware problem has become over the past two years. Despite growing attention from the White House and lawmakers, the million-dollar question remains: is the government of Russia supporting these attacks? Or – in some cases – is it even directly responsible for them?

A new report from Analyst1, a threat intelligence firm, looks into the matter. Their conclusion? “Yes.” The report, Absolute Ransom: Nation-State Ransomware, highlights several key findings that the company believes connect Russian intelligence agencies to prominent ransomware attacks, including the SolarWinds hack.

“We wanted to look at everything, from the bad guys’ side to what’s out there publicly,” DiMaggio told The Security Ledger. He said the company’s findings aren’t conclusive, but give him “medium confidence” that Russia’s government and intelligence agencies are involved with criminal ransomware outfits. “We have a bullet casing, the smell of gunpowder in the room, and a dead body, but we don’t have the gun itself,” DiMaggio said.

The point of the research was to “close the gaps” in what the world knows and doesn’t know so far about the connections between Russia’s government and the ransomware groups that operate within its borders. Others may then build upon the work Analyst1 has done, he said: “We want to get it out there so that others that have the visibility that I don’t have can fill in the gaps.”

Russian Cyber Criminal Named as Source of Massive Collection 1 Data Dump

Russian Intelligence Ties Run Deep

Connections between Russia’s intelligence services and Russia-based cybercriminal groups are well-established, DiMaggio said.

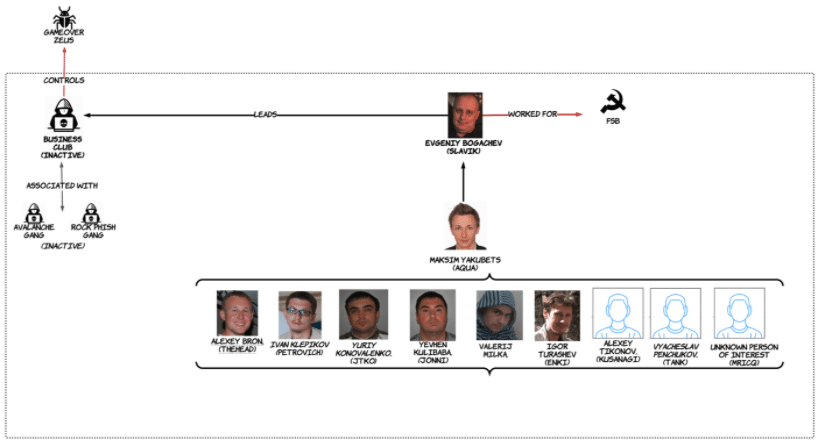

A former FSB officer, Evgeniy Bogachev (a.k.a “Slavik”, “Lucky 12345” and “Monstr”), developed Zeus, a banking trojan in 2007 and used it in cyberattacks beginning later in that year. Zeus would steal victims’ online banking passwords before draining money from their accounts. The success of the malware attracted the interest of other online criminal groups and gave rise to the Russian Business Club, an online cybercrime syndicate made up mostly of criminals from eastern Europe, including Russia, the Ukraine, and Moldova.

Bogachev was charged and named for his crimes in a 2014 Department of Justice indictment, which led to the dissolution of the Russian Business Club. But not before it gave birth to a new cybercriminal organization: EvilCorp, made up of former Business Club members, including its leader, Maksim Yakubets, another former FSB officer whose father-in-law Eduard Bendersky is also a career FSB officer who oversees an FSB veterans’ association and manages “private security agencies that provide services to state-owned companies,” Analyst1 noted.

More recently, the connections between cybercriminal groups and the Russian intelligence apparatus have expanded from staffing to operations. DiMaggio points to the analysis of two campaigns at the end of 2020 as an example.

Before SolarWinds: A Cyber Crime

Citing research done by the company TruSec, DiMaggio notes that in October of that year, EvilCorp used ransomware to compromise what is described as a “major corporation.” Two months later, the Silverfish cyber espionage group hacked the same organization. That group is believed to have conducted the colossal SolarWinds attack, which The Justice Department has attributed to the Russians.

Analyst1 said that a close analysis of the two attacks – one attributed to EvilCorp, the other to Silverfish – reveals several similarities. The Silverfish actors – alleged by the U.S. government to be Russian intelligence – followed the same, unique attack pattern as the earlier EvilCorp actors. That included everything from the Internet domains used for command and control and data exfiltration, to the “hands-on-keyboard” behavior of the threat actors within the environment to the scripts, tooling and malware beacons and other “IOCs” (or indicators of compromise). “They were exactly the same,” DiMaggio told The Security Ledger.

Still, the coincidence of the ransomware attack and the SolarWinds compromise allowed the Russian Government to have plausible deniability that they were not behind the espionage operations, because the face of the attack was a criminal entity, according to DiMaggio.

Talented Engineers Turned To Crime

As offensive cyber operations have become part and parcel of Russian spycraft and the country’s foreign policy, the country’s intelligence agencies have refined their operations, as well. While Russian military and intelligence organizations have a reputation for working in silos, the relationship between groups like the SVR, FSB, and GRU appears to be well-coordinated, DiMaggio said.

Episode 221: Biden Unmasked APT 40. But Does It Matter?

Information gleaned from criminal indictments related to the 2016 hack of the Democratic National Committee, for example, suggest that the Russian SVR has taken on the role of gaining initial access and “persistence” within target environments before handing it off to operational specialists in units like the GRU to plant malware, exfiltrate data and so on. That division of labor is still in place, he said.

The cybercriminal groups, led by former colleagues from the intelligence agencies, are just an extension of this ecosystem. They are likely encouraged to attack U.S. and Western interests: “As long as they (ransomware gangs) don’t attack Russia, they’re given sort of a blessing,” DiMaggio said.

The line between Russian intelligence and the ransomware groups is blurry, DiMaggio says. The Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) has gone as far as employing these same cybercriminals, sometimes by force, he said.

Episode 104: Mueller’s Cyber Eye on the Russian Guys also Reaper Drone Docs Stolen

Underlying the relationship is the unique circumstance of Russia, which is home to some of the world’s top engineering and computer programming talent, but an anemic domestic economy that provides few, legal employment options for talented programmers like Evgeniy Bogachev or Maksim Yakubets. Cybercrime is one of the best paying opportunities around, according to DiMaggio.

A Call for Change

The implications of Russia’s intelligence service working directly with cybercriminal groups are profound, DiMaggio said. First: it scrambles traditional distinctions between diplomacy and law enforcement. Looking at recent incidents like the SolarWinds attack, DiMaggio stressed that ransomware gangs, espionage groups, and the Russian government all left fingerprints in that attack and other, more recent attacks targeting America’s national security. This suggests that old ways of thinking need to be re-evaluated for a new era: “We cannot have that mentality of ‘this is crime and this is espionage and we can look at one as the lesser threat.’ We cannot do that.”

Instead of looking at Russia as a typical nation-state, DiMaggio urges us to look at the Kremlin with a different lens. “We definitely look at them in the same way that we look at ourselves, and in the same way that we might look at some of our other partners out there,” he said. “That’s just not the case with Russia. We have to start to look at them differently based on what we now know – that they are leveraging these relationships and we can see the damage done.”

Episode 177: The Power and Pitfalls of Threat Intelligence

DiMaggio is calling for an all-hands-on-deck effort to solve the ransomware problem: “We are not winning this fight. The way we thought of it yesterday is a problem, the way we think of it today is a little bit better.” But for tomorrow? “We have to change our mindset and change our resources we dedicate to stopping this because it’s only getting worse.”