In-brief: Colleges in the U.S. give away personally identifying data on millions of students each year as unregulated “directory information.” Job 1 when arriving on campus: opting out and protecting your data.

Editor’s note: This is cross posted from Digital Guardian’s Data Insider blog, where it first appeared and where you can read my post in its entirety.

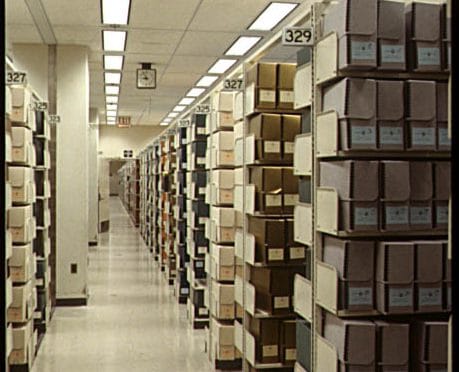

I arrived on campus to start my Freshman year 29 years ago this month. My brother and sister dropped me off on campus and helped me carry up an ungodly amount of stuff to my room including, if I remember, three or four weighty cardboard boxes of treasured vinyl albums. God forbid I should have to listen to cassettes for 10 months.

I don’t remember much about my first day on campus. But I believe one of my first responsibilities was to go to the Main building where most of the college’s administrative offices are and obtain my student photo ID that would serve as my library and meal card, etc. etc. This was 1988 and the Internet, such as it was, hadn’t reached students yet. Data privacy wasn’t a top concern. My student ID was, conveniently, my Social Security Number, and it was printed on the front of my ID card for everyone to see.

We live in a very different world today. Identity data like Social Security Numbers are widely recognized as valuable both to individuals and companies, and also to cyber-criminal groups interested in identity theft and other schemes. No more SSN doing double duty as student ID, employee ID, driver’s license number, and so on.

Moreover, private and public-sector organizations these days – from retailers to doctor’s offices and banks – are at least cognizant that they are stewards of a wide range of personal data on their customers. In some cases, as with healthcare and financial organizations, specific laws exist (like HIPAA) that govern and protect that data from casual disclosure or resale.

But you will be surprised to learn that, in the case of student data, that is mostly not the case, and that much of the data on you (or, if you’re a parent) you son and daughter that is collected by schools – the so-called student “directory data” — is free for the taking by, essentially, anyone who asks.

I learned this after speaking, in a recent podcast, with Leah Figueroa, a data analyst at a community college in Texas who has researched the issue. Figueroa was witness to and concerned by the many, wide-ranging requests for student data that her school was receiving. While many of these were for seemingly legitimate causes (such as research by other institutions), others were clearly commercial, and several lacked any context for or explanation of the purpose of the request whatsoever. In every case, however, her school turned over the goods: thousands, tens of thousands – even hundreds of thousands of records containing “directory data” on current and former students, no questions asked.

What kind of information are we talking about here? It really varies from school to school, but you can generally figure it out by Googling “FERPA” and limiting the search to the college you’re interested in. So, for me, that search was FERPA site:vassar.edu.

The term “FERPA” stands for the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974, a federal law that ostensibly protects student data like grades, but that exempts so-called “directory information” that may have seemed extraneous in 1974, but is now a gold mine for everyone from credit card companies to sub-prime lenders.

What’s in that “directory data”? It is what, in most every other context, would be considered “personally identifiable information” or PII. For my alma mater, it includes the student’s name, their student ID number, their address, telephone listing, electronic mail address, photograph, date and place of birth, their major, dates of attendance, class level, enrollment status, participation in officially recognized activities or sports, weight and height of members of athletic teams, degree received and honors awarded, and the most recent educational institution attended.

That’s pretty standard. MIT – hardly strangers to the notion of online privacy – includes an almost identical list of data in their description of student directory information. Both schools noted that they don’t need a student’s consent to release the information and provide instructions on suppressing the sharing of student directory information. MIT provides a link to the site to do it. My college just provides written instructions of how to adjust the sharing of directory information on the Student Directory page of the colleges website, leaving the student to figure out which page to navigate to on their own.

Very few students do so. “In any given data request, let’s say someone is asking for 40,000 records, we might have had 400 students opting out,” Figueroa told me in our conversation.