In-brief: Facebook on Thursday unveiled a new initiative to stamp out disinformation and ‘fake news,’ but University of Washington researcher Kate Starbird, who is studying online ‘counter narratives’ says that conspiracy theories and ‘truthers’ may be here to stay.

The social media giant Facebook on Thursday unveiled a new, online tool that it says will help its users spot misinformation and so-called “fake news” as part of a multi-prong attack on disinformation.

In a post, Adam Mosseri, the company’s News Feed Vice President said that Facebook was implementing steps to disrupt the economic incentives that drive fake news and giving its users new tools to make informed decisions when they encounter fake news stories.

But even as the company makes its stand, researchers studying the rise of fake news, conspiracy theories and organized disinformation campaigns say that the phenomenon may be far more difficult to unroot than it would seem.

The Security Ledger recently sat down with Kate Starbird, a researcher at the University of Washington. Kate has spent almost a decade studying what some call “crisis informatics:” the way that individuals use technology in the context of crisis events like bombings, shootings and natural disasters.

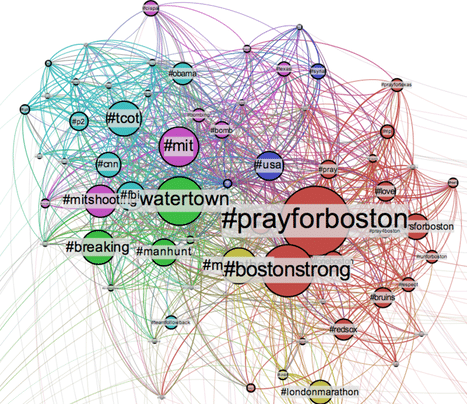

In the course of that research on data from platforms like Twitter and Reddit, Starbird frequently came across hoax stories and conspiracy theories, which often crop up in the immediate aftermath of traumatic events – part of a natural process that Starbird calls “sense making.” Rumors, after all, can turn out to be true – or false. In the heat of a crisis event, it’s often hard to know what information will pan out. “The majority of rumors are of that type,” she said.

But more recently, she and her colleagues started to notice to notice a new kind of crisis rumor -which they termed an “alternative narrative” rumor – that had a different signature than other types of rumors: more enduring and linked closely to overarching political themes that were independent of the crisis at hand.

“Alternative narrative rumors just look different on a lot of different dimensions,” she said.

One aspect is just the volume of messages and traffic promoting the idea over time. For a typical rumor, there would be a really quick spike and then and exponential decay – they look like long-tailed curves with really high spikes,” Starbird recalls. “These spike aren’t as high. It took them longer to grow…But once they built, they didn’t go away…they persisted over time,” she said. “Most crisis rumors would die out within a few hours or days. Once the truth became known they were debunked and went away. With these there was no debunking them. People would come and try but they would just counter that evidence or just come up with a new explanation.”

The conspiracy rumors were also citing a lot of different, external websites, Starbird said. These rumors -though about disparate events in disparate locations – also shared a common lexicon over time and across events. “Crisis actors,” “false flag” and “hoax” were common. “If we searched for terms like that we could find rumors related to just about any man-made event,” Starbird said.

Studying the websites that were often cited as sources of information supporting the conspiracies also revealed common themes: discussions of phenomena like “globalism,” “globalist,” “anti globalism.” Almost all these sites were supporting these anti-globalist notion, including anti-immigration and anti- free trade positions, even though the sites themselves might be catering to the left or right of the political spectrum.

Nationalist ideologies were also common – promulgated from a range of websites in the US, Europe as well as countries like Ukraine and Russia. Pro Russian views and websites, including Sputnik news and RT, were both part of the network of sites that amplified and girded conspiracies and counter narratives, even if they didn’t spawn them directly.

Needless to say, counter narratives, conspiracy theories and “truther” movements are often deeply offensive to communities that have already been traumatized by a violent or destructive event like a shooting (Sandy Hook, Orlando), terrorist attack (9/11) or natural disaster. Confronted with that anger and the raw emotion of those directly touched by events, conspiracy theories and theorists often look and sound ridiculous. (For a taste of that, check out this video of a Cambridge, Massachusetts, resident confronting an Infowars reporter about that site’s contention that the Marathon bombing was a “false flag” and the FBI was responsible).

Alas, technology and the Internet often mean that conspiracy theorists and the players in their conspiracies never look each other in the eye.

In a post on Medium.com in March, Starbird said that stamping out these counter narratives is nearly impossible, as those behind them just incorporate counter arguments into a complex, web like narrative of conspiracy, “false flag” operations and hoaxing. For example, stories in sites like the New York Times that explicitly counter the conspiracy narratives -like one about multiple shooters and paid actors at the site of the Orlando nightclub massacre – aren’t ignored by the conspiracy theorists and websites. In fact, they’re often cited, as evidence of a broad conspiracy that also encompasses mainstream media outlets.

Starbird is just at the start of her research into the fake news phenomenon, but she says that figuring out the landscape of this shadowy online network is critical, not just for academics, but for policymakers, journalists and others.

“Researchers, journalists, anyone who cares, we need to try to answer the question of ‘what is the impact,’ ‘who is doing the orchestration’ and ‘what is happening,'” Starbird said.

In this latest Security Ledger Podcast, Kate Starbird talks with Security Ledger Editor in Chief Paul Roberts about observing the growth of online rumoring, conspiracy theories and disinformation campaigns as a byproduct of her research in recent years, and why she thinks that many of the conspiracies floating around the Internet today may, in fact, be the work of a small number of players.