In-brief: companies bruised by massive denial of service attacks stemming from insecure Internet of Things devices may have to accept them as a ‘new normal,’ with no quick or easy fix in sight, experts agree.

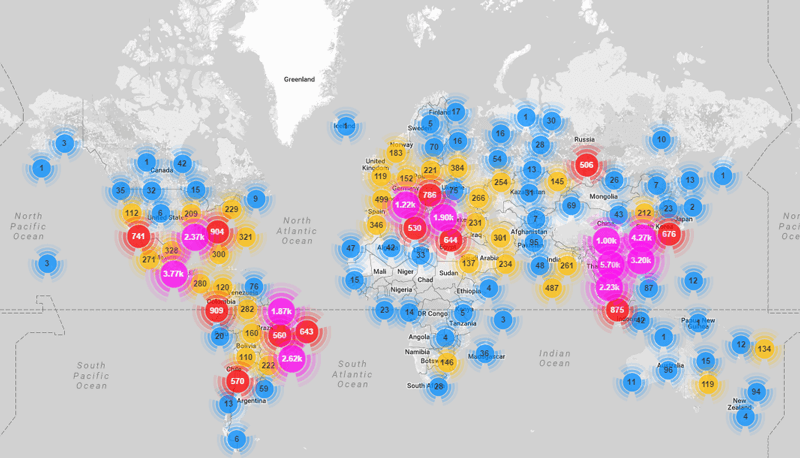

Three days after a motley collection of infected, Internet connected stuff called the “Mirai” botnet cut off access to some of the Internet’s most trafficked sites, little is known about the identities or motives of those who ordered and carried out the attack.

One thing has become clear, however: there is no easy or fast way to prevent more and even bigger attacks just like it from occurring. In fact, such attacks are almost guaranteed, as technology firms and regulators struggle to mount a response to Mirai and other botnets like it.

Xiongmai Technologies, the hardware and software vendor whose wares power many of the closed circuit TV cameras, digital video recorders (DVRs) and network video recorders (NVRs) enlisted in the Mirai botnet said it will recall affected devices, according to published reports.

The company’s technology figured prominently in a denial of service attack on Friday on Dyn, a New Hampshire based provider of managed Domain Name System services. Dyn counted Twitter, Spotify, CNN.com, The New York Times and other leading sites as customers.

As reported by The Security Ledger, an analysis of XiongMai’s technology by the firm Flashpoint found a number of features that make them easy targets for hackers. Among them: hard-coded the default credentials in the firmware, which customers are unable to change. Also, another flaw in the software XiongMai ships to manage its hardware components allows anyone with knowledge of the IP address of a device running the software to forego logging in at all.

Even before the attack on Dyn, the world’s media woke up to the problem of Internet of Things based botnets with large-scale denial of service attacks against Krebsonsecurity.com, a security blog, and the French hosting firm OVH, among other targets. But the problem of insecure, vulnerable Internet connected “things” has been building for years.

“I feel like this is just a manifestation of the security debt we’ve accumulated over many years,” said Joshua Corman, the director of the Cyber Statecraft Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Brent Scowcroft Center on Monday.

Market pressure to connect all manner of products to the Internet and to get new products to market quickly demanded that security features and secure infrastructure to support products after they’re deployed had to take a back seat. Companies and individuals who purchased and deployed the connected stuff didn’t “price” the security risk into their buying decision, nor did federal regulators in the US or elsewhere treat Internet of Things attacks as a pressing issue. That’s because attacks on such devices were more theory than reality and because easy measurements for IoT risk were not available, Corman said.

Even if XiongMai is committed to doing as it promised: replacing the compromised software with a more secure alternative, getting downstream customers like camera and DVR manufacturers to participate in a recall is a tall order. Currently, there is no authority to demand such an effort in the U.S., let alone across the scores of national borders that Mirai spans.

“Recalling a consumer device is ‘iffy ‘at best,” said Paul Vixie of Farsight Security, one of the authors of the Domain Name System protocol that helps users connect to resources on the Internet.

Consumers rarely fill out “warranty” cards that inform manufacturers who owns their products. And, unlike the automobile sector, there is little formal structure for recalls of the countless consumer goods sold in the U.S. and elsewhere. “When you talk about things like TVs and refrigerators, ownership of those devices is mostly anonymous,” Vixie said. “There’s no regulator who knows what’s out there, so you’re counting on the companies to know which of their products are affected and where they are.” At the low-end of the connected device market – where cameras and devices may be bought for $100 or less – there may not even be appetite among consumers and manufacturers to bother with a recall, Vixie said.

Allan Friedman, the Director of Cybersecurity Initiatives at the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) at the US Department of Commerce said that may be changing, with the Mirai botnet an inflection point.

“The problems with Xiongmai may mark the beginning of a sense of awareness,” he said. “Part of the role of government is to create room for discussion and help accelerate that discussion. This isn’t something that any company can solve by itself.”

Going forward, the U.S. government may be able to foster collaboration and information sharing between the information security community, device makers and the business and commercial sectors, he said.

Corman agreed, and said that the huge denial of service attacks against Krebsonsecurity and Dyn, among others, show that even low value endpoints like cameras and refrigerators can’t be ignored.

“We’ve been trying to figure out how to digest this problem one bite at a time, for example by focusing on safety critical systems,” he said. “What we saw on Friday is that we can’t neglect lower priority devices,” he said. As with diseases like Zika and Malaria, problems like denial of service attacks flourish in the “swamp” of insecure endpoints. Getting rid of the disease, then, means finding a way to drain that swamp, Corman argued.

“You have to pay attention to where these problems come from.”