In-brief: The battle of words over the security of devices by St. Jude Medical continued on Tuesday, as researchers from University of Michigan raised questions about claims that security researchers had actually “crashed” implantable pace makers.

The battle of words over warnings from a Wall Street trader about serious security flaws in implantable medical devices continued on Tuesday, as researchers from The University of Michigan are raising doubts about research that was used by the investment firm Muddy Waters to bet against (“short”) the stock of St. Jude Medical, a major medical device maker.

In a statement released on Tuesday, researcher Kevin Fu and Thomas Crawford of the Archimedes Center for Medical Device Research did not directly challenge the findings of the report by Muddy Waters and the firm MedSec, but did suggest that security experts whose research informed the report may have misinterpreted error messages from St. Jude devices. Rather than being evidence of a successful attack, the researchers say, the messages may have simply indicated that the home-monitored implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) device being tested was not properly connected to a patient.

“The U-M team reproduced error messages the report cites as evidence of a successful ‘crash attack’… but the messages are the same set of errors that display if the device isn’t properly plugged in,” the University said in a statement.

“We’re not saying the report is false. We’re saying it’s inconclusive because the evidence does not support their conclusions,” said Kevin Fu, U-M associate professor of computer science and engineering and director of the Archimedes Center for Medical Device Security. Fu is also co-founder of medical device security startup Virta Labs.

The conflict may come down to how different viewers interpret the same events. The behavior witnessed by the MedSec researchers and described in their report may not have been a security issue, but simply evidence of the device acting as designed, Fu and his colleagues say.

A defibrillator’s electrodes are connected to heart tissue via wires that are woven through blood vessels the wires are used both for sensing operations and to send shocks to the heart, if necessary. No surprise, when the defibrillator is not connected to a human host, the data transmitted by the device is quite different.

“When these wires are disconnected, the device generates a series of error messages: two indicate high impedance, and a third indicates that the pacemaker is interfering with itself,” said Denis Foo Kune, former U-M postdoctoral researcher and co-founder of Virta Labs” in a statement.

That behavior is very similar to what is described in the Muddy Waters report on St. Jude as evidence of a successful attack. “In a Crash Attack demonstration we witnessed on an ICD, the Crash Attack appears to have caused the device to pace at a rapid rate that could have adverse health consequences if it performed this way in a user,” the report reads.

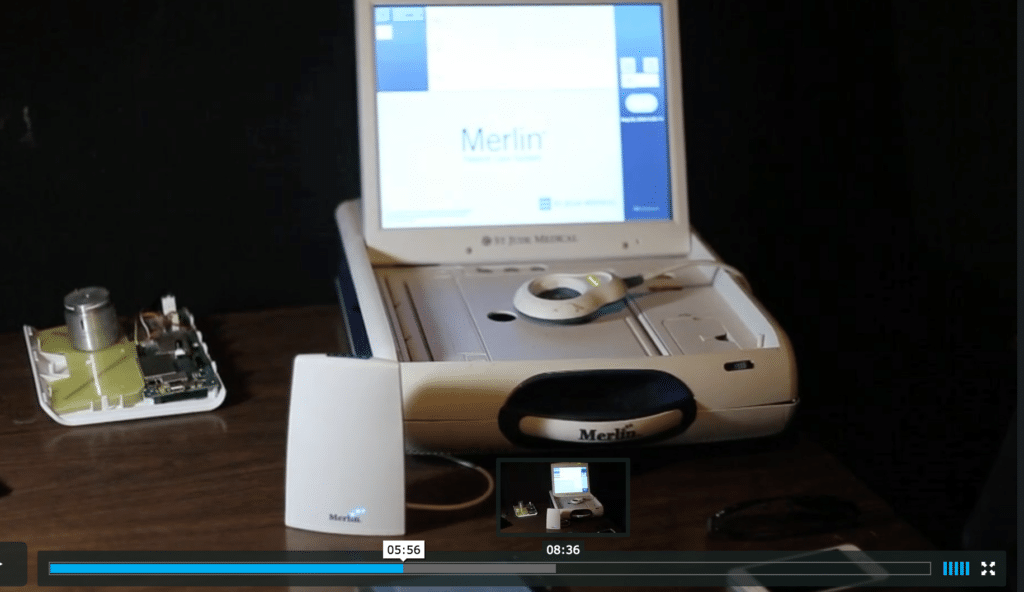

The report references a screen shot of a St. Jude programmer – the terminal that physicians use to tailor the device to a specific patient’s needs. The screenshot shows “the apparent malfunction. The red error messages above the lowest line are also indicators that the device is malfunctioning.”

But Fu and Kune looked at the same screen shot and saw something different.

“It looked like they just forgot to plug the wires in,” Fu told The Security Ledger. “Without clinical experience, it can be hard to interpret the results.”

Fu and his colleague set out to reproduce the exact condition captured in the screen shot of the St. Jude Programmer without modifying the device in any way and found that they could. While that doesn’t mean that the same condition couldn’t also be produced as a result of a software attack, it also means that the condition described by Muddy Waters and MedSec isn’t proof of a successful attack, either.

In a short statement, a MedSec spokesman said that the company was still reviewing the University of Michigan video and report. In response to a request for comment, the spokesman said that the University of Michigan report didn’t address the content of a video MedSec released on Monday to support its claims. The video shows a MedSec researcher launching a so-called “crash attack” against a St. Jude pacemaker.

The University of Michigan demonstration did not address the content of that video and was “obviously not an attempt to recreate the attack,” MedSec said.

However, St. Jude Medical issued a statement that continued its criticism of Muddy Waters and MedSec’s report, citing the latest MedSec video while making similar observations to the University of Michigan team.

The released video by Muddy Waters Capital and MedSec on Monday “actually demonstrated the Radio Frequency (RF) Telemetry Lockout security feature of our pacemakers – not a ‘crash’ as they claimed,” the company said in a statement.

“The video clearly shows a security feature, not a flaw,” said Phil Ebeling, vice president and chief technology officer at St. Jude Medical in a statement released to The Security Ledger. “The pacemaker is actually functioning as designed. If attacked, our pacemakers place themselves into a ‘safe’ mode to ensure the device continues to work, which further proves our commitment to safety and security.”

Fu said that the confusion may stem from security researchers who understand software security, but lack the medical knowledge to properly interpret the output of a pacemaker. While medical knowledge isn’t necessary to find vulnerabilities in a medical device or even hack them, it is critical to understanding the clinical implications of any software flaws and whether there is the possibility of causing harm to patients, as Muddy Waters and MedSec have alleged is the case with St. Jude.

“I read the report as saying ‘we found stuff but we don’t know what it means.’ So far, all the stuff they found is not as conclusive as it might seem,” Fu said.