In-brief: Old and outdated software continues to plague medical environments, opening the doors to infections and data loss, even by long-forgotten computer viruses, according to a report by the security firm TrapX.

Can we call it a chronic condition? Old and outdated software continues to plague medical environments, opening the doors to infections and data loss, even by long-forgotten computer viruses, according to a report by the security firm TrapX.

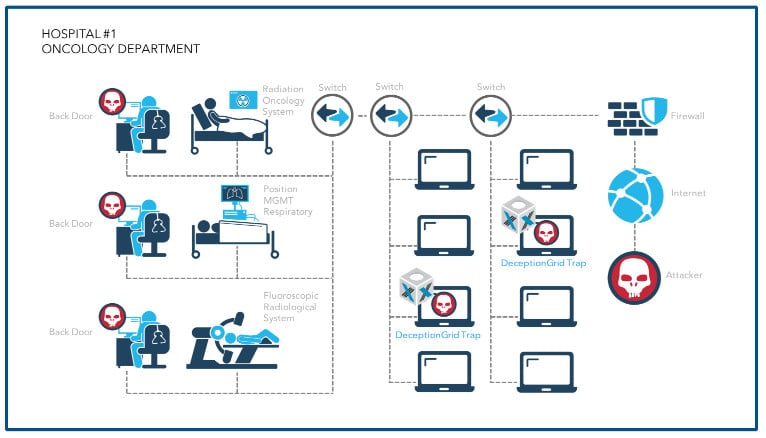

Vulnerable medical device software, often running on machines using outdated operating systems, like Microsoft’s Windows XP, are a chronic problem within healthcare environments. Attacks against healthcare organizations continue to “pivot around medical devices installed within the hospital’s hardwired networks,” providing backdoor access to hospital networks that allow attackers to work “virtually non-stop” within those environment.

The report comes a year after an earlier study, dubbed MEDJACK, also warned of widespread problems stemming from unpatched and insecure medical devices. The updated MEDJACK study offers little reason for optimism. You can download the report here. (Note: regwall.)

In-brief:

Security experts working for the firm TrapX said they found ample evidence that vulnerable medical devices were being targeted and used as a launch point for attacks on other, more sensitive areas of a medical network.

“We see malware jumping networking segments. They’ll go after an operating system first – Windows XP, mostly – but then locate devices on other parts of the network, said Anthony James, CEO of TrapX. More and more, TrapX said that attackers sometimes wrap sophisticated backdoor and persistence tools within older malicious programs, like the Conficker worm, as a kind of camouflage.

In one example the company documented in its report, malicious software was observed infecting one medical device, then jumping to what appeared to be a vulnerable server storing X-Ray images in another part of the hospital network. Often, hospitals know or suspect that attackers may be lurking on medical devices within their clinical environments, but lack the tools to be able to spot them or root them out.

Frequently, the medical device that serves as the initial target of the attack is not of interest, itself. Rather: it is low hanging fruit that allows attackers to establish a foothold and attack higher value assets that store patient health information or financial information.

“These attacks are becoming more aggressive,” James said. “They’re actively hunting other targets within the network.”

The report seems to support what experts like Kevin Fu, head of the Archimedes Center for medical device security in Ann Arbor, Michigan, have termed the “emergent properties” risk that hospitals face as different, insecure systems combine on a network.

Security experts note that hospitals face a number of challenges, as more (insecure) devices become connected to the Internet. Individual facilities – especially small hospitals – often lack the expertise and tools needed to manage their risk, Fu notes.

Budgets and salaries for information security staff in the healthcare field are lower compared with industries like banking, financial services and technology.

From the viewpoint of operations, hospitals are in a bind. Diagnostic equipment and other special purpose medical devices often are managed from computers running outdated, vulnerable and unsupported operating systems like Windows XP, which have all but been eliminated from enterprise networks. Device vendors often don’t offer updates to their software that would allow their customers to update management consoles to run newer and more secure versions of Windows. That, or hospital clinical and IT staff fear that doing so would jeopardize FDA certification of the device, said James – a commonly held belief that FDA administrators have taken pains to debunk in recent years.

Finally, the critical reliance of staff on life saving technologies is more than enough to push security concerns to the back burner, James said”Even if they have a device that they know is compromised, they can’t decommission it, because its critical for patient care,” he said. “Adversaries have realized this and see that these are soft targets holding valuable data.”

TrapX staff traced back attacks to compromised PCs associated with radiation oncology systems, PACS (picture archive and communications systems) that serve multiple different radiologic systems, The continued presence of unsupported and outdated machines leaves hospitals extremely vulnerable to attack – even using code designed to exploit known security issues that have long since been patched.

Hospitals have been frequent targets of cyber attacks in recent years. That includes a string of ransomware infections that has forced some facilities to pay hefty ransoms to cyber criminal groups in order to restore access to clinical systems.

Pingback: Code Blue: Thousands of Bugs Found on Medical Monitoring System | The Security Ledger